How many times have you heard them?

Two words.

“Happy New Year.”

Probably people have wished you a long, healthy life as well. Happy and healthy. I have to confess, every time I thought, healthy, fine, but there are so many other things that are important to me. That’s what I think when you’ve been working on our value canvas for a year, quality of life suddenly becomes much more than health, and yes I can testify, you come a bit of a ‘quality of life nerd’ as well 🙂

I don’t know about you, but to me Christmas and New Year’s is the time to take a look in the rear-view mirror. Before we look ahead, I want to take a quick look back gratefully on 2019, the year of build up.

With a dozen meetings – lunches, cakes or drinks – in 4 cities, Leuven, Antwerp, Ghent and a first one in Mechelen, we took our first steps in building our community, with several international connections already forged as well.

At these meet-ups I met all positive people who want to build a more value driven society and economy together, people who also give their own quality of life a boost. If there is one New Year’s message I’d like to share in these times of fake news, rising work pressure and climate change, there is a lot of hope and energy to put sustainable transformation further on track.

On our side, of course, we kept going. Our ‘Pension Plan’ workshop, which shows you how money influences your behaviour, was completed and already reached a few hundred people. The speakers from our network of speakers – active at 10 events – undoubtedly more. The first freelancers were guided in their search for a better quality of life and our Federation, a group of value driven freelancers, started the guidance process for value driven entrepreneurs. Together with 3 other partners we started LoReCo, an ambitious 3-year project where we want to install a complementary city currency in a Flemish city, built on a new money design.

Of course, not everything went smoothly. The development of Slingshot, the company model on which we were working, was delayed because we ran into a few legal – mainly tax – challenges. The board game didn’t get any further because of unforeseen issues with the financing of the prototype. We will leave both obstacles behind us in 2020.

2020 will be the year where we finalize some products and solutions, the Slingshot corporate model, the board game and Tribeforce, the software that supports building sustainable organizations.

We will also roll out our existing activities more structurally in Flanders, if all goes well we will be active in 5 cities at the end of this year with an antenna in each city, the first partnerships have been concluded in the meantime. Finally, we will furtherbuild up the foundations for our international presence For example, our site will be translated into 7 languages and we are actively looking for value-driven talent to further develop the Federation internationally.

As you can see, a challenging menu, we are looking forward to it! We hope your year will also be full of plans bringing you enthusiasm, joy and meaning.

On behalf of everyone in our organisation, a happy 2020.

Bruno

string(3) "yes" NULL

In an earlier article, I built a case against the idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI), even though I’m in favour of the principles and values on which the idea is built. Does this sound paradoxical to you?

The reason is simple though. We can craft a solution to take the best a UBI has to offer (freedom and security), and then combine it with other elements toincrease the quality of our lives even further.

A very important bonus is that it will also reduce the resistance which so many people have against the idea of a UBI, because it will reduce inequality even further and will cost less.

What if our society could guarantee that everybody would have sufficient money to live a good life from birth onwards? This would be a dynamic happiness income.

A dynamic happiness income is an income that guarantees to support the quality of our daily lives to the utmost extent. It is rooted in the idea that we can have the basics of our survival covered, and also that we can all live a truly abundant, high-quality life. It also looks into the real needs of every individual.

A dynamic happiness income is more about enabling you to enjoy life in all its dimensions than it is about preventing the struggle of survival. In a sense, it is even more ambitious than a universal basic income.

You may have noticed that the typical characteristics such as equality and universality found in a universal basic income are absent. This is not because they are forgotten; it is because they are not there, and with good reason.

Fairness is central to our actions, and is something that we can even see in our ancestors, the primates.

Without any doubt, a UBI takes many steps to reduce inequality between people. The good news is that we can have even more of it. If we give everybody the same unconditionally, we reduce inequality. However, we will still be confronted with a situation where inequality will be at a level that we don’t want.

Studies by Dan Ariely, a well-known behavioural economist, show that the differences we considered to be ‘just’ are much smaller than those we are facing now.

The truth is that our system isn’t fair. The reality is that the majority of people need to go to work to pay for the bills just to meet their basic needs. More and more people are subsequently struggling and individual differences are becoming ever bigger.

Assuming that we want a ‘just’ system, we need to adjust the idea of a universal basic income, so that it fits our current reality. Accepting these differences enables us to turn the imminent problems we are facing into an opportunity for a high-quality life, because, unlike what you may think, there has never been more potential to upgrade our world for the better.

To achieve increased fairness, to reduce ‘waste’ and to align more closely with those things that drive our happiness, a dynamic happiness income introduces the following three adjustments to the universal basic income:

A dynamic happiness income does not make abstraction of the inequalities we have in our societies; it embraces them, even though that tastes like a nasty syrup.

A dynamic happiness income is therefore not for everybody. A dynamic happiness income takes into account your current income level and its source. If you earn a sufficiently high income that is not linked to your time, i.e. a passive income, such as an income from a house rental or financial products, you are not receiving anything or at least not the full amount you would get without that passive income.

Because you already have the means to live a high-quality life without having to work a full-time job, you already have the sense of security and the freedom to choose how you spend your time. Good for you!

That’s fair, right?

As George Orwell said in Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. (Vol. 5. sage, 1980), “All societies are unequal, but some are more unequal than others.” That is why we need a system where the income we give to people is dynamic.

The hand we’re dealt with to play in life is different for all of us. You may have married a rich specimen, or maybe you inherited a house. Maybe you live alone, maybe you don’t. Maybe you have an illness or maybe you’re just five years old. All of these things impact the amount you are receiving.

That’s why a dynamic happiness income takes into account our differences and situations throughout our lives.

Taking into account individual differences is essential to achieve a system that maximises the potential for abundance for all of us. When we focus on the real needs a person has and adjust the amount to those needs, this strengthens our sense of fairness, and consequently increases efficiency. We spend money where it is needed and avoid spending where it is not.

Firstly, we cannot create happiness. Happiness comes from within, and the best we can do is to try to maximise the circumstances for happiness. We can only craft the scene for us to have the potential to live a high-quality life.

Therefore, the question is, “How should this scene look?” This is where, as a society, we can choose to set standards. Just as a staff member sets the stage, we can use a dynamic happiness income to support those needs that drive the well-being of people, even if those people do not value them as such.

That is why you cannot spend the dynamic happiness income freely. To be clear, this choice is made to support freedom, rather than curbing it. We can use a dynamic happiness income to drive choices that support the well-being of all of us, making it possible for us all to thrive in our own unique ways.

In case you still find this hard to accept, let me ask you this: “Are you happy that a single person would spend his or her universal basic income on cigarettes and excessive amounts of alcohol, things the person uses to numb insecurity and which destroy their health?

If you think it is more desirable to use this income to give this single person safety, basic comfort, decent food, access to healthcare, even if he or she doesn’t really value these things, then we are on the same page. The only limitation to freedom people should be willing to accept is to those things that science has shown to drive our well-being.

Although the idea of a UBI has been discussed for centuries, it is still not here. Don’t let the experiments currently running in The Netherlands and Finland fool you. They do not capture the essence of a universal basic income. Yes, they are valuable in their own right, but they are temporary and the amount is too low to ensure that people feel at ease.

So, here we are. Will we wait for a couple of centuries more to install a system providing security and freedom or will we install a pragmatic and fairer upgrade of a universal basic income?

Let’s not forget that the original reason we invented an economic system in the first place was to increase the quality of our lives. A dynamic happiness income offers us a tool to do exactly that, and in this lifetime.

Curious how we can upgrade our economic system so it supports the quality of your life and of those you care for?

In the book “Happonomy, Roadmap to Utopia”, Bruno Delepierre takes you on a 300 page journey to explore how work, money and technology impacts the quality of your life. Expect insightful analyses, intimate portraits and 35 daring recipes for upgrade. Interested? Take a look!

string(3) "yes" NULL

If there is one thing that drives a high-quality life, it is taking the time to enjoy what you have accomplished, reflect upon the mistakes you have made and dream about the road ahead. A new year is the perfect opportunity to do exactly that. Writing down these words also helps me to answer the following question which we were asked many times this year: “So, what exactly are you guys working on?”

Without further ado, here is a recap of 2018 and a look ahead to the year to come.

As with every novel idea, it can be a bit scary to truly commit to a new way of thinking. The road we took last year was still paved with a variety of questions and uncertainties. As you know, it is the journey rather than the goal that matters, so figuring out the answers and overcoming insecurities were quite enjoyable actually. What was still a bit foggy at the beginning of last year became crystal clear during the course of 2018.

Starting from a single question, about how we can increase the quality of life of people, we identified two focal points, and these two points are in essence the mission of our organisation, i.e., increase awareness about those things which colour people’s lives and develop solutions for how to deploy work, money and technology so they support our quality of life and not detract from it.

This resulted in the development of three core building blocks, or ‘models’ if that’s what you’d like to call them.

The Happonomy Value Canvas enables individuals and organisations alike to determine those things that are valuable to them.

The Sustainable Money System is a new monetary design with the idea of solving most of the problems we experience with our current monetary system.

Finally, there is ‘Slingshot’, a legal blueprint to realign intrinsic value with money and work. The model can be applied as a novel approach to crafting shareholder agreements that put value first both in a start-up phase and in a more mature phase.

Last year, we initiated several projects to raise awareness about the quality of life and the roles which work, money and technology have to play. The speakers in our speaker network were present at five events, inspiring hundreds and at the same time giving away 3,500 euros via their efforts. We organised over twenty-five test sessions of our board game showing the impact of money on our choices and our quality of life. The book called ‘Roadmap to Utopia’ was also steadily distributed around.

As for real ‘solutions’, the brunt of the work focused on the answer to the question about how we can build value-driven organisations. We gave workshops to government officials and social entrepreneurs, and we even finalised the first version of a fully fledged technology solution called Tribeforce to build sustainable organisations and maximise the value of work.

The last quarter of the year was devoted to test-driving a trajectory for value-driven freelancers and entrepreneurs, and this trajectory worked wonderfully well. Out of this, our Federation was born, which is a group of business experts who support the creation of value-driven organisations.

If you’re curious, just explore the brand new expanded version of our website. Yes, we’ve been busy.

Above all though, 2018 was the year of countless talks, laughter and challenging ideas from wildly diverse people. There was no agenda, no ego, and no “networking”, just regular people meeting up to have a chat about the good life and their experiences, struggles or insights of the roles money, work and technology have to play.

2018 was a good year…

Needless to say in 2019, we are excited to build on the foundations of last year. If anything, we are going to continue to work on bringing the solutions we have built to life and drive awareness further. The board game will be launched, very likely with a Kickstarter campaign, the development of the software will be furthered and we will continue to grow The Federation, our network of value-driven business experts.

To do so, we’ll build a new organisation next to the non-profit organisation which is built on the Slingshot model, unless we stumble into legal boundaries, of course. It will be deployed to develop the technology further and trigger our ‘implementation’ activities. If you want to join us, just reach out.

In 2019, two new initiatives will complement our already nicely-filled agenda. The first one is focused on education; if all goes well, we will craft an educational package for economy students to complement the existing economy lessons. Our goal is to increase awareness and critical thinking about our current system.

Secondly, we are going to organise more encounters, with one notable initiative being the Happonomy nerd-outs, which are expert sessions where people can discuss topics freely such as basic income, the role of artificial intelligence or the quality of life.

So, there you have it, that is our menu for 2019. We hope that your plans are filled with memories in the making.

Wishing you a high-quality year,

Bruno

Want more? Don’t be sad that the article is over! We got plenty of other exciting stuff to share with you. Subscribe to our bi-monthly newsletter and we’ll keep you up to date with our latest news!

string(3) "yes" NULLPlastic has had a bad reputation in the ecological society for years. This is mainly because it takes hundreds of years to decompose and it is considered to be a huge pollutant in our dying world. The only other supposed pollutants that have a worse reputation than plastic are greenhouse emissions. So, how can a villain become a hero? The answer can only be by taking out a larger villain and preventing a huge disaster.

Carbon negative plastic is produced from greenhouse gases. Essentially, the process involves capturing and degrading methane with a biocatalyst. If this was truly as simple as it sounds, then everybody would be doing it; it is actually a complicated procedure that requires very sophisticated equipment.

After the biocatalyst does its job, what you get are basic components such as carbon, oxygen and hydrogen. Once you have these three, you are on the easy street to producing plastic and so much more.

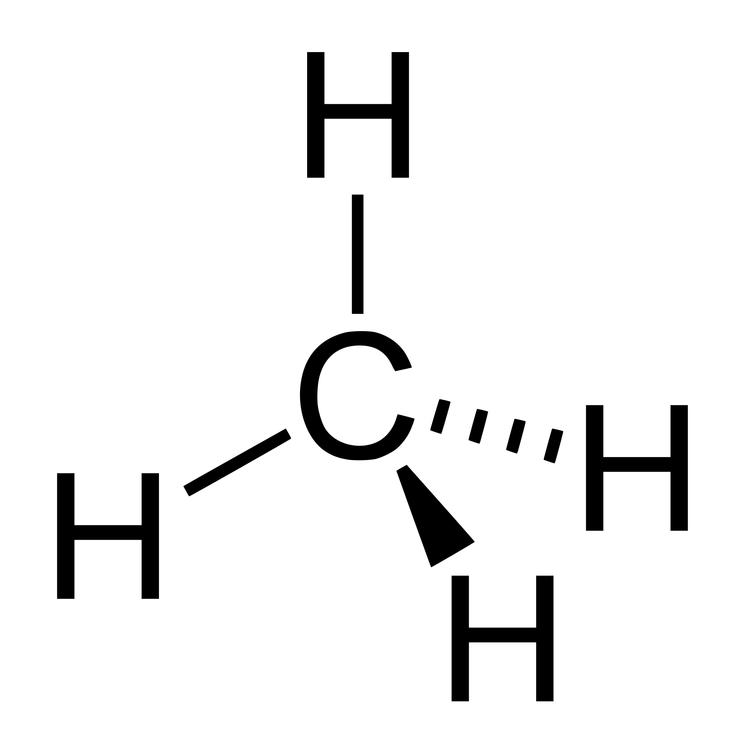

Methane atom before being split into carbon, oxygen and hydrogen.

Basically, carbon negative plastic is taking pollution out of the air and putting it to good use. Plastic is virtually indestructible in today’s world, so the least it can do is relieve the world of another pollutant. Greenhouse gases threaten us every day and are the main factors that contribute to global warming. Saving the world by producing carbon negative plastic is a crazy idea that just might work, as it is also an idea that generates profit.

Carbon negative plastic is not a new idea. It has existed for a decade and it has evolved substantially over the years. The greatest challenge was to produce plastic in a cost effective way. It took researchers at Newlight Technologies as much as ten years to be able to produce plastic at competitive prices.

Now, they have a shot at getting a huge chunk out of a $370 billion industry. That is how much plastic is worth these days and the race is on. Securing competitive prices without governmental help is a huge step and if governments decide to support this eco-friendly production method, carbon negative plastic may even come at a lower price than the competition.

Regardless of how things play out, there always has to be a losing side. In this case, the losing side will probably be the big oil and fracking companies and any others that provide fossil fuels for the creation of plastic. Considering that all of them are part of the environmental problem, experiencing a loss from the solution provided seems fair. However, when there is a lot of money at stake, nobody expects huge companies to go down without a fight.

Companies that stand to lose are the big oil and fracking companies and those that deal with fossil fuels.

Carbon negative plastic does not have to rely solely on its low price to compete on the market. This new innovative plastic can also compete with its quality. Newlight’s AirCarbon (which is a high-performance thermoplastic) is already being used to create many different hard-plastic products. Nothing is put to waste as even the resin is used to create plastic pellets, which are just as good as those that are oil-based, yet more cost effective.

So far, what has been achieved is simply amazing. We have finally created something that is not only cost-effective but also good for the environment. The production of this type of plastic can even make the air in large industrial cities breathable again. However, the road ahead is long and filled with many challenges. Currently, carbon negative plastic is produced in a small factory run by a total of fourteen people. Even though there have already been large investments in this technology, its application needs to grow far more before we can see a positive impact on the environment.

Want to find out in what way sustaining our environment impacts our quality of life? We got you covered! Find out more about sustainability and letting go.

string(3) "yes" NULL string(3) "yes"Mollit duis Lorem amet veniam minim ad.Voluptate commodo labore aliqua quis esse aliqua.Veniam tempor elit velit non.